The Gate of St. Mark

According to a Venetian document from 1229, another gate stood about seventy-seven feet east of the Porta Hebraica, also known as the Gate of the Perama. This entrance was called the Gate of St. Mark (Porta San Marci). The name most likely originated during the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–1261), when the city was under the control of Western crusaders and Venetians. St. Mark, being the patron saint of Venice, naturally lent his name to this gateway as a mark of Venetian influence in the area Porta Hebraica and Gate of Perama.

It is uncertain whether this gate was a newly opened entrance during the Latin period or simply an older Byzantine gate renamed in honor of St. Mark. Unfortunately, no surviving Byzantine sources mention a gate by this name, and archaeological evidence has not confirmed whether it existed before the conquest. However, the presence of the Venetian community in this district and their deep devotion to St. Mark make it quite likely that they named or rededicated an existing gate to symbolize their power and religious identity.

The Gate of the Hikanatissa

Farther to the east, another gate once stood, about 115 pikes (roughly 170 meters) before reaching Bagtche Kapoussi, near the modern-day Seraglio area. This entrance was known as the Gate of the Hikanatissa (Πύλη τῆς Ἱκανάτισσης). The name also applied to the surrounding quarter, which was referred to in historical texts as the District of the Hikanatissa.

The term “Hikanatissa” is best understood as being related to the Hikanati, a corps of palace guards or imperial troops that served in Constantinople during the Byzantine period. It was common in Byzantine naming traditions for areas and buildings to take their titles from military units or government offices located nearby. Therefore, the Gate of the Hikanatissa likely stood near the residence or barracks of these elite guards, or near a palace building associated with them.

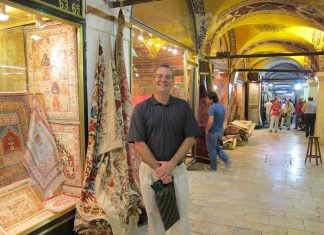

The historian Codinus also mentions a “Residence of the Kanatissa”, which probably refers to the same district. This connection supports the idea that both the gate and the quarter took their names from this important military institution Guided Tours Turkey.

The Surrounding Merchant Quarters

Between the Gate of the Perama and the Gate of the Hikanatissa, there stretched a lively commercial area filled with foreign merchant colonies. The section immediately east of the Perama was known as the quarter of the Amalfitans, traders from Amalfi, an important maritime republic in southern Italy. These merchants had been active in Constantinople since at least the eleventh century, conducting trade between Byzantium and the Mediterranean. Their quarter included homes, storehouses, and small churches dedicated to Western saints.

At the Gate of the Hikanatissa, the Pisan quarter began. The Pisans, like the Venetians and Genoese, were granted permission by the Byzantine emperors to maintain their own separate district for trade and residence. These Italian colonies were strategically placed along the Golden Horn, close to the sea walls, where ships could easily unload goods from the Mediterranean.

Thus, this stretch of the harbour wall—from the Gate of the Perama to the Gate of the Hikanatissa—formed one of the most international and commercially active parts of Constantinople. The area was a meeting point of cultures: Byzantine, Venetian, Pisan, Amalfitan, and later, Genoese.

The Changing Cityscape

Over the centuries, the names and functions of these gates changed as political control shifted and communities moved. The Gate of St. Mark, for instance, reflects a brief but important moment when Venice exerted immense influence over the city. The Gate of the Hikanatissa, by contrast, preserves the memory of a more traditional Byzantine order, when imperial troops and officials dominated life within the city walls.

Together, these gates illustrate how the topography of Constantinople was shaped not only by emperors and armies but also by merchants, pilgrims, and soldiers from many lands. Each new name or district reflected a chapter in the city’s long and complex history, from the Byzantine Empire to the Latin occupation and beyond.